You have an upset customer with a really thorny problem on your Django-powered website. Your customer used your help ticket system and reported their woe. You’ve done your due diligence and have already checked:

- The logs from your site show nothing interesting related to the customer’s actions

- The error tracking system reveals no exceptions from what the customer did

- The customer’s description doesn’t contain enough info to diagnose the problem fully

- The experiments in your dev environment have not worked to replicate the problem

What can you do? Solving difficult software problems often requires the ability to reproduce the issue. As the saying goes, you can learn a lot by walking a mile in someone else’s shoes.

If you could access your customer’s account and see what they see, you might be able to deduce what went wrong by seeing the issue for yourself. Django takes the sensible approach of not storing plain text passwords in your database so you can’t log in as your customer. Or can you? With django-hijack, you can impersonate a user account to experience what your customer experiences.

In the remainder of this article, we’ll look at my experience with integrating django-hijack to provide this capability for one of my personal side projects. By the time we’re done, I think you’ll have a good idea of how to add django-hijack to your own project if you need to support your customers by impersonating their accounts.

Hello Hijack!

We need to start by installing django-hijack in your project.

(venv) $ pip install django-hijack

Once you’ve installed the package

from PyPI,

we must add it to INSTALLED_APPS

and include some URLs

which the package uses

for its purposes.

django-hijack relies

on two separate applications,

hijack

and a compat app

that hijack depends on.

# project/settings.py

INSTALLED_APPS = [

...

'hijack',

'compat',

...

]

# project/urls.py

urlpatterns = [

...

path("hijack/", include("hijack.urls")),

...

]

There’s one final setting that I added for my project, but we’ll see it later.

Hijacked Templates

When you’re impersonating a customer’s account, you want to have very obvious signs that you’re not in your own account. This should aid you from doing something stupid like deleting your customer’s data.

django-hijack gives us some tools for our templates to help check if the logged in session is hijacked or not. With these features, you can modify your templates to get your attention when you’re masquerading as your customer.

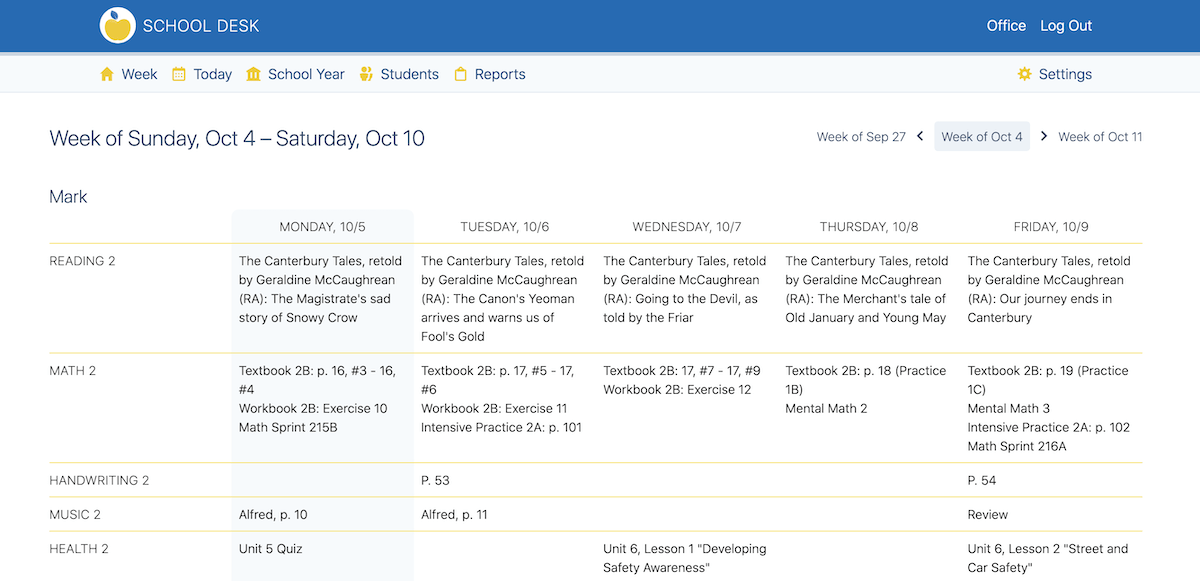

On the project where I included django-hijack, my theme color is blue. My default user interface looks like:

School Desk standard UI

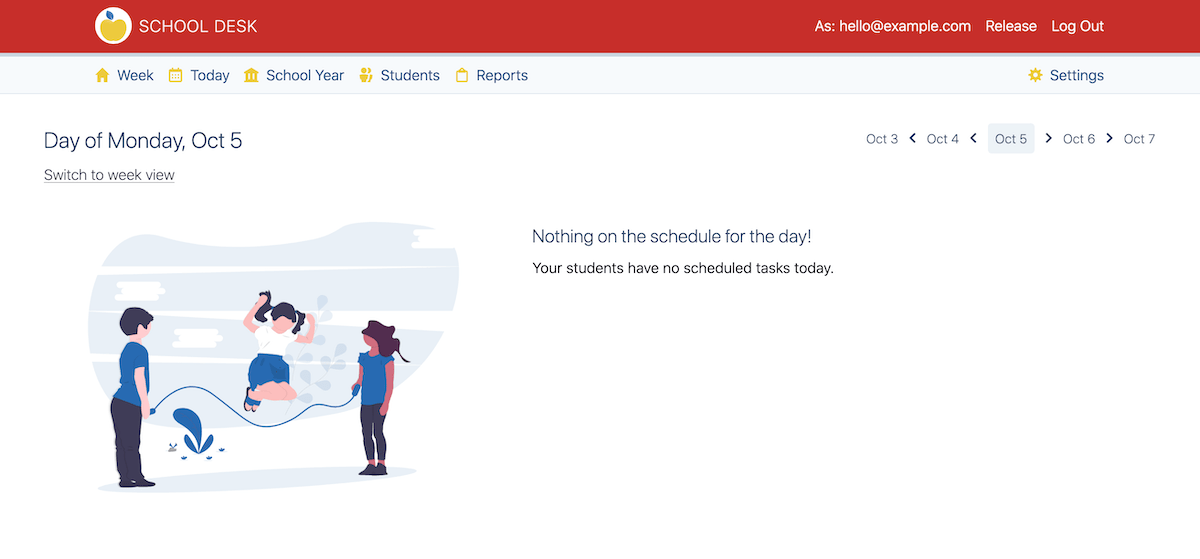

I used django-hijack’s built-in template tags to make the default navigation red instead of blue and added some context of who I am impersonating when hijacking a customer’s account. Here’s a sample of the output (note: this is from my development machine and you’re not looking at someone’s real data):

School Desk hijacked UI

To make this change, I modified a navigation bar template in my project. The template code showing the relevant part is:

{% load hijack_tags %}

{% if request|is_hijacked %}

<div class="mr-4 font-light">

As: {{ user.email }}

</div>

<form class="mr-4" method="POST" action="{% url 'hijack:release_hijack' %}">

{% csrf_token %}

<button class="hover:underline font-light" type="submit">Release</button>

</form>

{% endif %}

First,

we must be certain

that the hijack_tags are loaded.

This gives access to an is_hijacked template filter.

The filter is designed

to get the request object provided

by the django.template.context_processor.request context processor.

That context processor has the singular job

of adding the request to the context.

# django/template/context_processors.py

...

def request(request):

return {'request': request}

When is_hijacked returns True,

I modified the user interface

to show the customer’s email address

and the form that let’s me release the hijacking

to return to my user account.

There’s also a bit of template code

that picks a red CSS class

instead of a blue CSS class

based off of is_hijacked

that I’m not bothering

to show in the example code.

Who Hijacks?

If any user could impersonate another user, this would be a terrible system. How can someone hijack another customer’s account? By default, django-hijack will only permit user’s with superuser access to hijack an account.

This configuration can be controlled by settings, but this is a very reasonable default to me. Limiting the ability to hijack to a very small subset is a good security stance when considering the tradeoffs of an impersonation feature.

To initiate a hijack, the library provides a couple of URL endpoints that can be POSTed too, but I wanted a more accessible way to start the process.

In my project, I created an admin action that gives me, as the superuser, the ability to hijack a customer’s account. The code looks like:

# users/admin.py

from django.contrib import admin

from django.contrib.auth import get_user_model

from django.contrib.auth.admin import UserAdmin as AuthUserAdmin

from hijack.helpers import login_user

@admin.register(get_user_model())

class UserAdmin(AuthUserAdmin):

actions = ["hijack_user"]

def hijack_user(self, request, queryset):

"""Hijack a user."""

if len(queryset) == 1:

user = queryset[0]

return login_user(request, user)

A hijack request can only apply

to a single customer account

so my admin action checks

that only one user was selected.

Then the code uses the login_user helper

from django-hijack

which will do the proper authorization checking

and redirect to the customer’s account

if the staff user has the right permissions

(i.e., the staff user using the admin is a superuser).

The hijack:release_hijack URL

that I used in the template

from the previous section

also needs some configuration

to return a hijacker’s account

to an appropriate destination

when finished with the impersonation.

Since I used an admin action as my entry point,

I decided that it should be my exit point as well.

The settings addition uses the HIJACK_LOGOUT_REDIRECT_URL setting.

# project/settings.py

HIJACK_LOGOUT_REDIRECT_URL = "/<admin site prefix>/users/user/"

With this setting, I can return to the same admin page that I started with.

Ethical Considerations

Should you do this on your project?

“Hijacking,” “impersonating,” and “masquerading” are potentially scary terms when we’re talking about customer accounts and data.

I firmly believe that technology can be used for good and bad purposes. I’m not blind to the fact that hijacking a customer’s account can be seen as an invasion of privacy.

In light of that, I think we, as software developers, need to consider the ethical implications of our actions.

Using a tool like django-hijack is a last resort. I started this article by noting a wide variety of conditions that I would consider before instigating a hijacked session. Let’s see them again as a reminder:

- Did you check all the logs?

- Did you check all the error monitoring tools?

- Did you listen to your customer and think through the problem?

- Did you attempt to replicate the problem in a development environment first?

Impersonating a customer with this tool is intended to help the customer when other options aren’t able to produce results. If you’ve exhausted all of your other options, then I feel that acting on the customer’s behalf can be an acceptable option.

When logging in as a customer, I still think it’s best to respect privacy as much as I can. The goal of an impersonation session is to observe and diagnose a problem, then get out. Any actions taken should be limited to the steps reported by the customer in an attempt to observe their problem in a live context.

If you’re on a larger team, there are also additional steps that you can take to be accountable for your actions (or a teammate’s actions) while accessing a customer account.

django-hijack includes a couple of custom Django signals

that you can use

to monitor hijack usage.

The signals, hijack_started and hijack_ended,

will report the users IDs

of both the hijacker and the hijacked customer account.

This data could be added to audit logging

of some kind

and monitored for abuse.

In an ideal world, we wouldn’t require such systems and could trust all team members, but having accountability built-in to a system is a good alternative for a world that obviously isn’t ideal.

Lastly, I’ll note that some restrictions might be in place on your app by your Privacy Policy or the laws in your country. I won’t pretend to be a lawyer so make sure you do your due diligence with your local legal folk.

As software developers, we want to help our customers and make a good product, and we should strive to act ethically in those pursuits.

Summary

This article covered django-hijack, a powerful tool for acting on your customer’s behalf when helping them with a problem.

I showed how I set this up for one of my projects. We examined:

- The initial setup

- How to configure the templates to show a hijacked session

- How to extend the Django

Useradmin to start a hijacked session - The ethical considerations to ponder before using such a powerful tool

I hope you’ve learned something and can apply django-hijack to your project to help your customers as best you can.

If you have questions or enjoyed this article, please feel free to message me on X at @mblayman or share if you think others might be interested too.